Malcolm Graham writes about his journey after the Mother Emanuel Church shooting

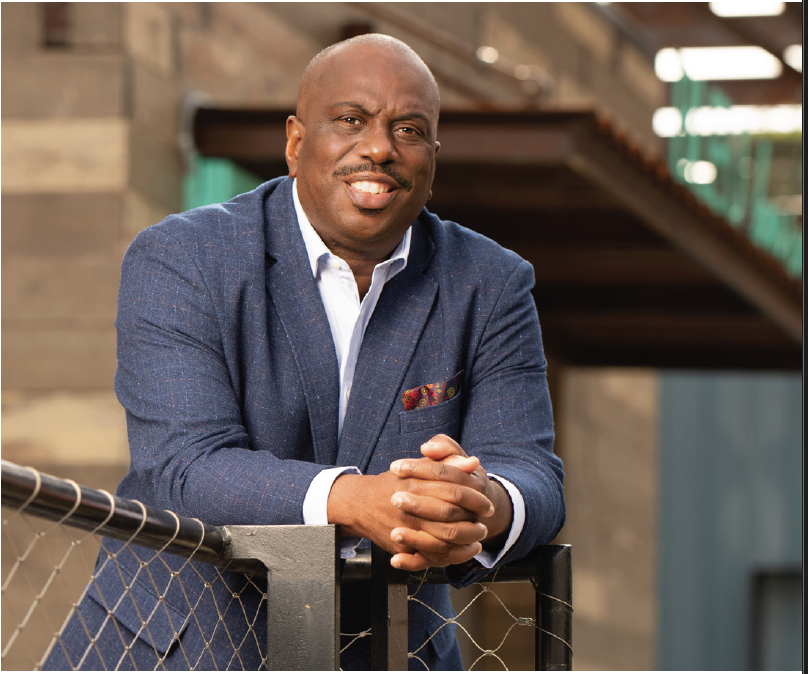

By Angela Lindsay

When a young white man walked into the historical Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston under the guise of joining church members in their Bible study and shot and killed nine of them, the shock across the nation was palpable.

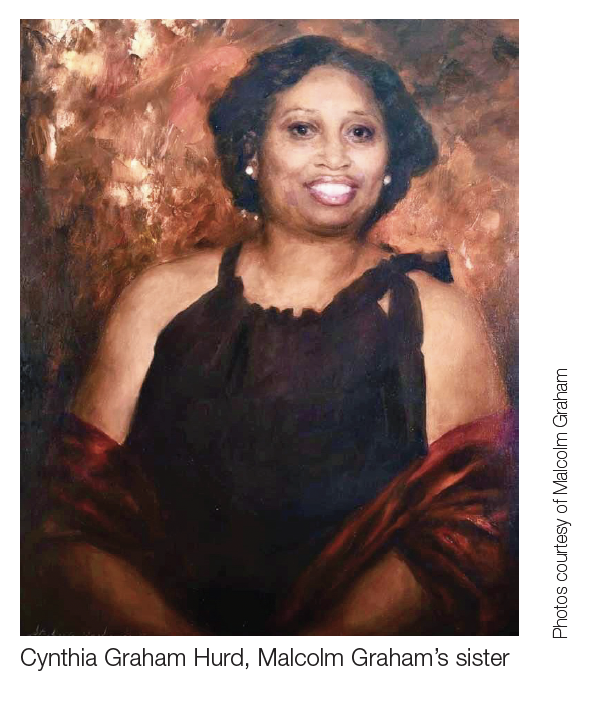

For those in the Charlotte area, the event took an even more tragic turn when it was discovered that one of the victims, Cynthia Graham Hurd, was the sister of long-time local public servant and current Charlotte City Council member since 2019, the Hon. Malcolm Graham.

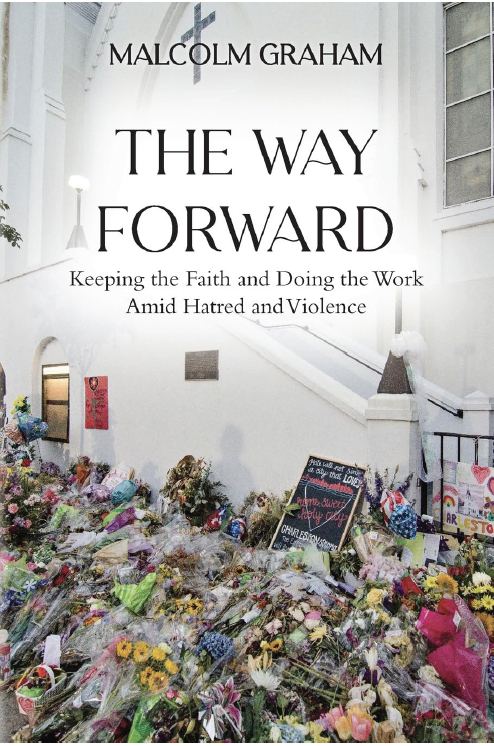

I sat down with Councilman Graham to discuss his new book, “The Way Forward: Keeping the Faith and Doing the Work Amid Hatred and Violence,” wherein he channels his pain, perspective and perseverance in a way that he hopes will help and heal others as it has himself.

Angela Lindsay: How did the decision to write this book come about, and why was it important for you to do so?

Malcolm Graham: I decided to write “The Way Forward” to observe the 10th anniversary of the tragedy that forever changed my life and the lives of so many others . . . Cynthia dedicated her life to learning and literacy as a librarian, and today, the Cynthia Graham Hurd St. Andrews Regional Library stands as a testament to her legacy of service, compassion and knowledge.

In addition, I felt a deep calling to honor her memory in a way that would both preserve history and offer perspective. I wanted a book about her — and about that moment in time — to have a permanent place in the library that bears her name. More than that, I wanted to provide future generations of my family, including my grandsons Carter and Ashton, and others who will never have the chance to know Cynthia personally, with a firsthand account of what happened and how our family journeyed through grief, resilience and purpose.

Lindsay: What did the writing journey look like?

Graham: The journey to writing “The Way Forward” was both emotional and deeply personal. It took about a year to complete, but in many ways, it was 10 years in the making. There were several starts and stops along the way — moments when I had to pause, reflect and gather the emotional strength to continue. Writing about such a painful chapter of my life required space, grace and time.

Much of the process involved research and conversations. I interviewed many individuals who were directly and indirectly connected to the tragedy — family members, friends, clergy, community leaders and others who played a role in the events that unfolded in Charleston. I also revisited newspaper clippings, editorials and video footage from that period to ensure accuracy and context. Those materials brought back powerful memories, but they also reminded me how far we’ve come as a family and as a community.

My approach to writing was rooted in honesty and transparency. I didn’t want to polish or perfect the pain. I wanted to tell the truth — my truth — about the experience, the loss and ultimately, the resilience that followed. Writing “The Way Forward” was not just about recounting events; it was about finding meaning, purpose and hope through the process of reflection.

Lindsay: How would you describe the writing process for you — therapeutic, cathartic, revelatory or something else?

Graham: For me, the writing process was deeply therapeutic. In the years following the tragedy, I never took time for formal counseling. There was simply too much happening all at once — first, the shock of losing my sister, Cynthia, then the responsibility of helping plan her homegoing service, and soon after, being thrust into a national conversation about forgiveness, justice and reconciliation. There were public debates about the Confederate flag, family matters to attend to, and even moments on the national stage, including meeting President Obama and the First Lady. Lastly, it was the trial where I testified as a character witness for my sister.

In the midst of all that, I never truly paused to process my own grief. My focus was always outward — on keeping my family strong, supporting my community, and doing the work necessary to honor Cynthia’s life and legacy. I poured myself into service and leadership, but rarely into self-reflection.

Writing “The Way Forward” changed that. It became a safe space for me to slow down; to look back and to face the emotions I had quietly carried for nearly a decade. Through the process of writing, I was finally able to grieve, to heal and to make peace with moments I hadn’t allowed myself to fully feel before.

Lindsay: What did writing the book teach you about yourself?

Graham: It taught me more about myself than I ever expected. For nearly 10 years, I had been so focused on moving forward — keeping my family strong, serving my community and honoring Cynthia’s legacy — that I never really stopped to ask how I was doing. Through the writing process, I learned that healing doesn’t come from constant motion; it comes from allowing yourself to be still long enough to feel, to remember and to process.

I discovered that I had carried a great deal of unspoken pain — not because I wanted to hide it, but because I felt a responsibility to be strong for everyone else. Putting those emotions on paper helped me understand that vulnerability is not a weakness; it’s a form of courage. It takes strength to confront your own heart.

I also learned that forgiveness, which I had spoken about publicly for years, is not a single act — it’s a journey. Writing forced me to revisit difficult moments and emotions I thought I had already resolved. In doing so, I realized that forgiveness continues to evolve; it grows with you as you grow.

Lindsay: How did you initially feel when you first heard the news about what happened at Emanuel AME Church? Can you describe how your family — immediate and extended — were and still are affected?

Graham: I wrote about this moment in the book — the exact instant when I knew something was happening back home. I was getting ready for bed when the television, tuned to CNN, interrupted its broadcast with breaking news. There had been a shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, and reports were saying that several people were dead.

I froze. Emanuel isn’t just any church to me — it’s my family’s spiritual home. I was born and raised in Charleston, and for more than 50 years, my family has been connected to that church. My grandmother and my mother sang in the choir there, and my brothers Robert, Gilbert and Melvin, and sisters Cynthia and Jackie, and I grew up within those very walls. It was a sacred place — a place of love, community and faith.

My first instinct was to call Cynthia to find out what was going on. She didn’t answer. I told myself she was probably trying to make sense of everything or helping others. But as the minutes passed, the news coverage grew more alarming. About 40 minutes later, I received a call from my niece, Megan. Her voice was trembling. She told me they couldn’t find Aunt Cynthia and that she had likely attended Bible study that night. From that moment forward, our family’s tragedy began to unfold.

I felt stunned — almost outside of myself. Even though I was miles away from Charleston, I could feel the weight of what was happening as if I were standing right there in that church. I remember feeling both helpless and heartbroken, yet somehow focused, trying to process the unthinkable.

For my family, the loss of Cynthia was — and still is — immeasurable. She was the heart of our family; the one who connected everyone, who remembered every birthday, who showed up for everyone. Her absence created a void that can never be filled.

Over the past decade, we’ve each carried that grief in our own way. But we’ve also carried her spirit — her kindness, her intellect and her belief in service. The pain of losing her never disappears, but our love for her and the way she lived her life, continues to guide us. The tragedy shattered us, but her legacy has helped us rebuild.

Lindsay: How have your views on loss, grieving and forgiveness been changed or expanded through this process?

Graham: My views on loss, grieving and forgiveness have evolved in complex and, at times, uncomfortable ways. I’ve come to understand that forgiveness is not simple — it’s not a single act or a moral performance. It’s a deeply personal journey, and one that I’m still on.

People often ask if I’ve forgiven the man who murdered my sister and eight others that night. The truth is, I can’t. How do you forgive hatred — not just an individual act, but the centuries of racism, discrimination and violence that made such an act possible? What happened at Mother Emanuel wasn’t only an attack on nine innocent people; it was an attack on an entire race of people. The shooter himself said he wanted to start a race war.

Ten years later, as I look at where we are as a nation, I can’t help but ask: has that war already begun, and we simply refuse to call it what it is? We see attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion. We see attacks on truth in education, on voting rights, on the very progress that generations before us fought and died to achieve. These are not isolated moments — they are reflections of a deeper struggle for justice and equality that continues.

Grieving for me has also meant reckoning with that reality — understanding that my sister’s death is tied to a much larger story about America’s unfinished work.

But even amid that pain and anger, I’ve also learned that love and purpose can coexist with grief. My faith tells me that I may not be able to forgive today, but I can still work for healing, justice and hope. My way of honoring Cynthia — and the eight others — is by continuing the fight for a world where such hate has no place. That, to me, is a form of grace.

Lindsay: How has Mother Emanuel AME Church changed since the incident? Do you ever go to the church to visit?

Graham: Yes, I visit Mother Emanuel quite often. For me, it’s not just a church — it’s sacred ground. Every visit is emotional, but it’s also grounding. It’s a place where tragedy and triumph coexist, where faith continues to rise above hate.

Over the past 10 years, Mother Emanuel has remained a symbol of resilience, grace and unwavering faith. The church continues to welcome worshippers from around the world who come to pay their respects, to pray, and to draw strength from the congregation’s remarkable spirit of perseverance. The members have carried on the legacy of their ancestors — turning pain into purpose, and sorrow into service.

On June 12 of this year, I hosted a national town hall meeting at Mother Emanuel to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the tragedy. It was a moving and powerful evening that included live music, heartfelt tributes, and a panel discussion led by my good friend Bakari Sellers. The event was not about reliving the pain of that night — it was about celebrating how Cynthia lived, not how she died. We honored her legacy and the legacies of all nine victims by focusing on their faith, their service and the light they brought into the world.

Mother Emanuel continues to stand as a living testament to that light — a place where the doors remain open, and the message remains clear: Love is stronger than hate, and faith is stronger than fear.

Lindsay: How has this experience shaped who you are going forward as a public servant and your views on how to best serve our community?

Graham: This experience has profoundly shaped the way I serve and the way I lead. It has made me more empathetic, more present, and more deeply aware of the pain that so many families in our community live with every day. When I meet with families who have lost loved ones to violence — whether through gun violence or other acts of senseless tragedy — I can relate to their grief in a very real and personal way. I know what it feels like to have your world suddenly turned upside down, to have to find faith in the middle of heartbreak, and to try to make sense of something that can never fully be explained.

Because of that, I try to approach those moments with both compassion and conviction — to show them that faith in God can sustain us, but also that faith requires work. James 2 tells us that “faith without works is dead,” and I believe that to my core. We can pray for peace, but we also have to create policies that make peace possible. We can lean on our faith for strength, but we must also act — to strengthen gun safety laws, to support victims of domestic violence, to invest in community programs that prevent violence before it begins.

Going forward, I’m committed to serving with both faith and action — helping families heal, helping communities find hope and doing the hard work necessary to make Charlotte a safer, more compassionate city for everyone.

Lindsay: What do you want readers to take away from this book? What advice would you give them on how to cope in the face of adversity and tragedy?

Graham: Coping with tragedy isn’t just about enduring the pain — it’s about finding ways to honor it through meaningful action. My advice to readers is to let your grief or your fear fuel your purpose. Stand up, show up and work toward change, whether in your family, your neighborhood or your community.