By Brenda Porter-Rockwell

With more than 8,600 food scientists in the U.S., African Americans account for only 4% of that population, according to career industry website, Zippia.com. Enter Charlotte-based nonprofit George Washington Carver Food Research Institute Agriculture STEAM Academy. This two-week summer immersion program for high schoolers is more call to action to increase representation in food science careers than traditional summer camp.

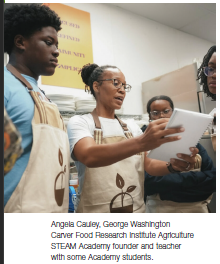

“This industry is the second largest industry in the world. There’s plenty of opportunity and space for our children to be able to have wonderful careers — whether they’re working internally for companies or externally having their own business,” said food scientist and GWCFRI/Academy co-founder, Angela Cauley.

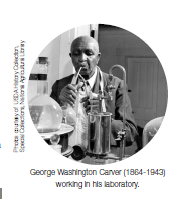

The foundation’s name and mission are a nod to the extraordinary work of George Washington Carver — best known for his peanut research. But Carver was also a general agricultural innovator based on what we know today as science, technology, engineering, arts and math (STEAM) techniques.

Carver was a leading researcher at Tuskegee Institute. He’s best known for promoting crop rotation and sustainable farming in the South, introducing alternative crops like peanuts, sweet potatoes and soybeans to restore soil depleted by cotton.

Cauley said she and her husband/business partner, Dr. Ian Blount, an agribusiness and applied economist, hope the students gain career insights as well as practical takeaways through STEAM exercises.

The academy launched more than a decade ago, after Cauley and Blount sold their for-profit food science business and transitioned their expertise into a non-profit model that helps fill the pipeline for agricultural and food science innovators.

Cauley said the students explore, “The impact of food, where food comes from, how it arrives on the shelves and gets to you. You’re learning about how to eat to live to optimize your own health. If we plant those seeds inside a student, then they can go back and talk to their parents and their friends and create that change.”

Real-life problems, real-life solutions

Day one of this summer’s academy began with a personality assessment designed to introduce food science pathways.

“The scholars were able to look at [results] then understand ‘what are my likes, my dislikes, my strengths, my weaknesses …’ and really get to the sole purpose of what it is that they’re put on this earth to do. And if it’s in the industry, that’s great. If it’s not, then that’s still okay,” explained Cauley.

Real-life problem solving with a corporate partner is a large part of the STEAM curriculum. This summer’s students brainstormed and pitched ideas that could help MANA Nutrition in Matthews find a new outlet for its product.

MANA had been manufacturing and distributing a peanut butter-based ready-to-eat supplemental nutrition pack for malnourished individuals in developing nations through a humanitarian food aid partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). But with the shuttering of all USAID work earlier this year, MANA needed a new audience for its product. Stepping up to the challenge, students pitched several solutions.

“We discussed the nutritional aspects and ramifications — like why is it okay for this product going abroad to have the sugar content that it had, and what is the detriment to consumers here in the United States based on a typical American diet?” Cauley said.

One team proposed reformulating to avoid using peanuts in a U.S.-targeted product, as peanuts are a big allergen issue here at home compared to0 other countries. The students proposed substituting navy beans for peanuts.

“The creativity was off the chains!” added Blount.

Blount said a typical product cycle time from conception to product launch can be 18- to 24 months. In under two weeks, students developed a new supply chain, packaging prototypes, logos, pricing models and 30-second commercial bites for MANA.

“They did what your huge conglomerates do. Not to the level of granularity and specificity, but at the end of the day they created a product from the whole life cycle in eight days,” said Blount.

Hands-on career exposure opens new possibilities

Stepping outside the classroom, some of the students headed to the Institute of Food Technologists’ (IFT) event called “IFT | first Event and Expo” in Chicago in mid-July. From the IFT stage, students shared highlights from their two weeks at the Academy, including how they’re planning to use their newfound knowledge. Students walked the show floor and networked with companies, colleges and universities. While in the Windy City, students also toured a beef tallow plant to see how the product is made.

“It was going to be two full conference days of just … Wow!” said Cauley.

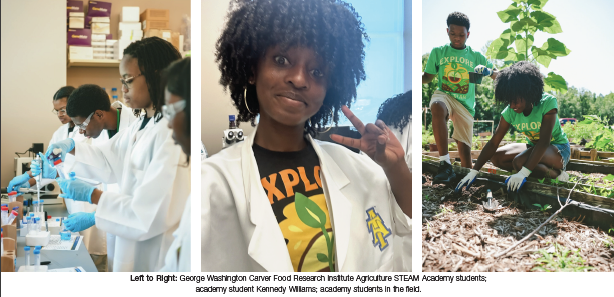

Kennedy Williams, 16, of Charlotte, attended the camp in 2024 and again in 2025.

“One unforgettable experience from the camp was visiting a lab that’s used by several colleges and universities in North Carolina. We had the opportunity to use real lab materials, conduct titration experiments and participate in hands-on activities that gave us a true sense of what food scientists do every day,” said Williams. The teen also found value in touring a Black-owned farm.

“Seeing how much effort goes into producing the food we eat daily was eye-opening. I gained a new respect for farmers and for the incredible design of the land God created,” said Williams, adding that the has made her reconsider her future college major.

“I had planned to study biology on a pre-med track. But now I’m considering minoring in food science or incorporating it into my studies in some way because it relates to so many careers,” Williams said.

Williams eagerly recommended the academy to all students.

“Even if you’re not originally interested in food science, I highly recommend giving the camp a try,” said Williams.