By Hope Yancey

It’s a raw December afternoon, and Barbara Taylor, director of the Matthews Heritage Museum in downtown Matthews, is at work inside doing some sleuthing.

Unfurled on her desk are copies of old maps. She wants to know more about a historic African American neighborhood about a half-mile from her North Trade Street office.

Taylor is completing a project she began in January 2018, to research and document Tank Town. She’s using census records, newspaper articles, oral histories of residents and their descendants and other resources. The quest has taken her to a library at UNC Charlotte and the main branch of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library.

Truliant Federal Credit Union’s Charitable Contributions Committee supported her endeavor with a donation of $2,000. “This project was fascinating to our committee and really stood out as something unique and different,” Renee Shipko, community engagement supervisor, wrote in an email. “One of our focus areas is arts and culture, and we believe the idea of unearthing the African American story in Matthews and supporting the research for this project would enhance the history of the Matthews community.”

Taylor plans to make her findings accessible to the public through an in-depth temporary exhibit at the museum, hopefully to be followed by a smaller, permanent exhibit. There also will be instructional materials geared to third-graders in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, she said.

Taylor notes most of the museum’s exhibits haven’t required such extensive research. “It’s consumed me,” she says of the yearlong project.

Tank Town’s history likely traces to 1879, 14 years after the Civil War ended. Dr. J.S. Gribble, a white physician, owned 130 acres of land and was selling several parcels. How he amassed the land and to whom it was transferred are threads in Taylor’s research.

Of note in Tank Town was a Rosenwald School, one of a group of schools for African American students started by Julius Rosenwald, philanthropist and head of Sears, Roebuck & Co.

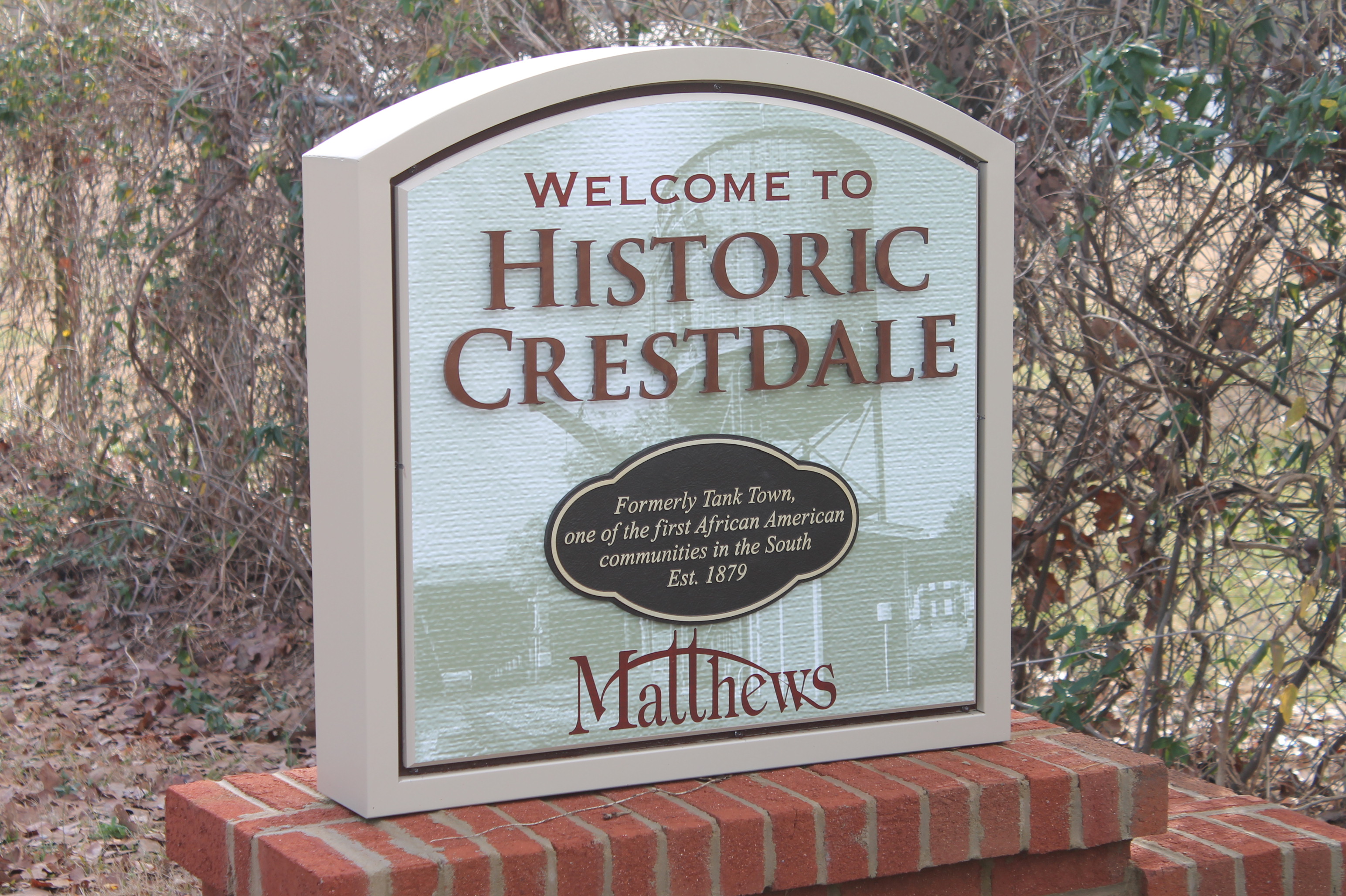

Tank Town, later known as Crestdale, is adjacent to the Sportsplex at Matthews, a modern complex of athletic facilities near Interstate 485. The name “Tank Town” derived from a wooden water tank that once stood, supplying steam locomotives. No one seems to know why the “Crestdale” name was selected, Taylor says. Over time, the community had its own entertainment in the form of “juke joints” – halls where jukeboxes played music – several churches, fraternal organizations, a store and more.

Follow signage for the Sportsplex along East Charles Street from downtown Matthews to enter Crestdale. A roadside sign denotes the boundary.

Matthews annexed Crestdale in 1988, and extended city water and sewer services, improving living conditions. One longtime resident of Crestdale is Harvey Boyd, 74. His late father, Sam, worked for the Seaboard Air Line Railroad and was known unofficially as the “Mayor of Crestdale” for his neighborhood advocacy. Prior to annexation, residents drew water from wells and a few active springs, Boyd says in a phone interview. Without indoor plumbing, they relied on outhouses. At Halloween, mischief-makers sometimes overturned the outhouses, Boyd noted wryly.

Boyd’s late mother, Viola, was a hairdresser and proprietor of a beauty shop she ran from home. Her skills attracted customers from a wide area, he recalls. Boyd lives in his childhood home. His bedroom is a former “section house” built for railroad employees and moved to the site by his parents, who made it part of their house.

Boyd studied at Central Piedmont Community College and Howard University. His career in art, advertising and graphic design took him around the country and abroad. He returned home to care for his parents, who have since died.

People knew each other in Crestdale. “It was a big family,” Boyd says.

To learn more, visit http://www.matthewsheritagemuseum.org for information on the museum, including hours of operation and cost of admission.