Chablis Dandridge works to save Charlotte’s at-risk youth from the cycle of crime and punishment he experienced.

By Sonja Whitemon

A student at Rocky River High School was shot and killed after stepping off his school bus last fall. He played tight end on the football team, and he was planning to graduate this year. The murder happened near The Reserve of Canyon Hills community in Charlotte, where homes can sell for upwards of $400,000. Two juveniles were arrested for the murder; at least one suspect was only 16 years old.

If this doesn’t shock you, that may not be a surprise. Sadly, we may be getting desensitized to the occurrences of gun violence among Black youth in and around Charlotte, seemingly every day. If it seems that Black children are increasingly the perpetrators and victims of gun violence, it’s because it’s true.

The entire country is struggling with rising gun violence, especially among Black youth. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, Black children die from gun violence at a substantially higher rate than children of any other race or heritage. Although Black children represent only 14 percent of children in the United States, they account for 46 percent of youth deaths by firearms.

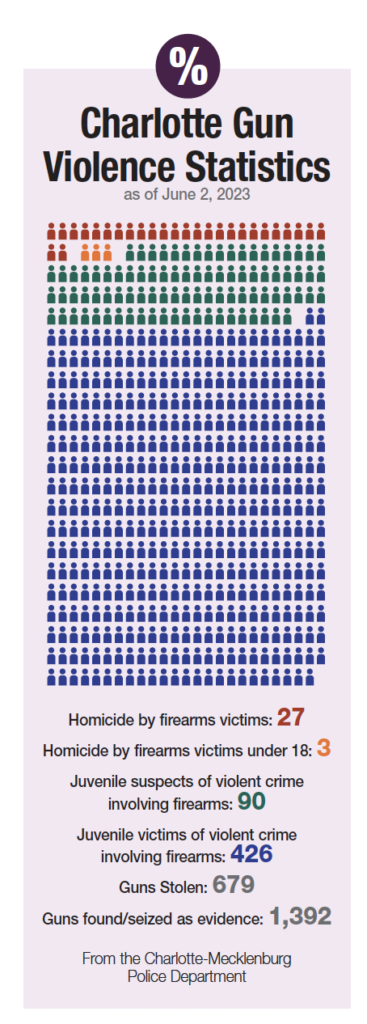

In Charlotte, during the first half of 2023, there were at least 426 juvenile victims of violent crimes involving firearms and at least 90 juvenile suspects of violent crimes involving firearms. The obvious question is: Where are children getting guns?

According to one Facebook user, the answer is simple — “break-ins.” In his words, “The young population in [Charlotte and [other cities] can get you a gun faster than u (sic) can order a pizza.” The Charlotte Mecklenburg Police Department agrees and says teens get guns in a number of ways but the most common seems to be theft. The issue is not going away and is actually getting worse, according to CMPD.

In 2021, CMPD formed the crime gun suppression team to combat gun violence. The team was merged from the former Gang Unit, Shooting into Occupied Property Task Force and the Targeted Response and Apprehension Unit. In its first year, the team seized 283 firearms, an increase of 83 percent, and 36 firearms, an increase of 57 percent over 2021.

One theory to explain the prevalence of gun violence among Black youth is that their world is saturated with sounds, images and concepts that glorify gun violence. Movies, social media live streaming/tagging and, of course, music offer a nonstop infusion of violent, anti-social behavior.

Chablis Dandridge knows that world all too well. By the age of 14, he was already living a life of delinquency. At 18, he was shot four times during an attempted robbery; as a result, he has been confined to a wheelchair ever since. Even so, Dandridge continued with his criminal life, mostly in drug trafficking, leading to incarceration for the majority of his adult life. He left prison for the last time just five years ago. Now 46, he is committed to saving youth from his fate.

Today, Dandridge works with juveniles to keep them from making decisions that lead to incarceration. He also works with juveniles already incarcerated and after release. Dandridge agrees that although there are multiple other factors, music is a big contributor to the epidemic of violence we are seeing. “It is the culture today and the music,” he said.

Rap music from the 1980s has evolved and spawned aggressive, rage-filled versions of itself. During a class he teaches in the jail system, Dandridge learned about a new kind of rap — beyond gangsta rap. It’s called drill music. The lyrics are even more violent, and they are difficult for a layperson to comprehend, written with extremely fractured sentences and isolated words that seem to do nothing more than provide a platform for references to guns, violence and blatant disrespect for women. “This rap is predicated on killing,” said Dandridge.

“See, I am Wonder Mike, and I’d like to say hello to the Black, to the white, the red and the brown, the purple and yellow…” No! This is not your Sugar Hill Gang. The evolution of rap music from the 80s is dramatic and disturbing.

Here is a sample of the messages that are amping up many Black teens and preteens:

“I got all the Glocks cause back then I had to get ahead of it … had to turn that boy into Swiss cheese.”

“F— a shooter because I am one. … got murder all in my eyes, you see, it’s torture in my heart.”

“I’ll rob you, b—-, I’ll shoot you, b—-, I’ll jack you out your paper.”

Clearly, not all Black youth are being influenced by guns and violence in entertainment, but there is a subset of juveniles who are locked into lives with limited parental supervision or positive role models, and they have a constant diet of messages promoting misogyny, guns, violence, hate and revenge that too often does not lead to positive outcomes.