By John Burton Jr.

By the time seven-year-old Kwamé Ryan looked up from his seat at Ontario Place in Canada that summer evening in 1977, his fate was sealed.

The Houston Grand Opera’s production of “Porgy and Bess” was unfolding before him — that quintessentially Black American opera about the fictional Catfish Row in South Carolina, love and loss, and Black resilience. But young Kwamé wasn’t just moved by the story. His eyes were locked on the man at the front with the baton in his hand, summoning magic from musicians. “I want to do what that guy is doing,” he told his mother. She believed him. When the family returned to Trinidad from their Toronto vacation, she bought him a used piano.

Nearly 50 years later, Ryan stands as music director of the Charlotte Symphony Orchestra. He is one of the few Black conductors leading a major American orchestra. But his journey to the podium reads less like a story of barrier-breaking and more like a masterclass in trusting one’s artistic compass — even when the path seems improbable.

His father was a university political science professor. His mother was a secondary school English teacher who lived a second life on stage as an actress. The young Ryan spent countless evenings at her rehearsals, scribbling notes and sending “suggestions” to directors through his mother. “I think I must have been a pretty precocious child,” Ryan said. It was the theatrical environment — the collaboration, the creative problem-solving, the communal pursuit of something greater imprinted on his artistic DNA.

Another formative moment that shaped his sonic imagination was the movie “Star Wars” that debuted in the summer of 1977. It wasn’t the story or special effects but John Williams’ orchestral score that felt otherworldly to him. Watching Zubin Mehta conduct the New York Philharmonic on television with Leontyne Price and Itzhak Perlman— an Indian maestro, a Black soprano and a Jewish violinist creating art together.

“It planted the happily misguided idea,” Ryan said. “That it was entirely normal for an Indian conductor to lead a world-class orchestra and a Black diva to be performing alongside him,” he added.

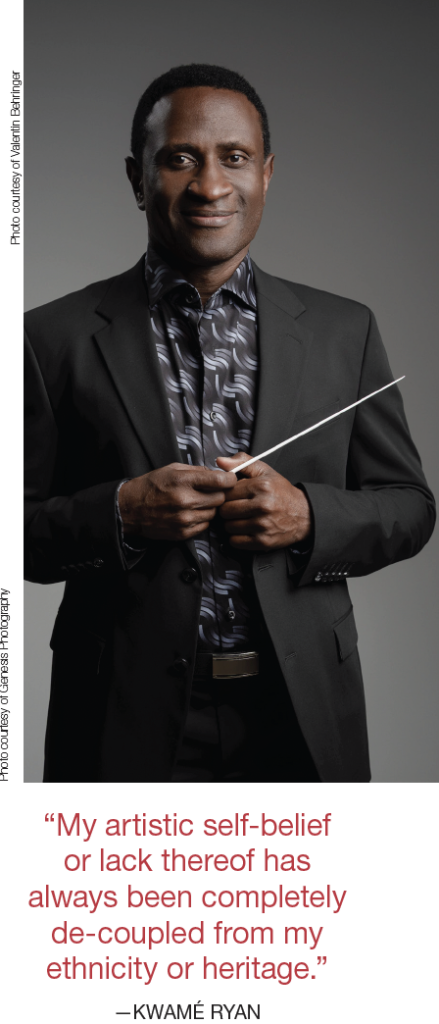

Ask Ryan about being one of the few Black conductors in his position, and his answer disrupts the expected narrative. “My artistic self-belief or lack thereof has always been completely de-coupled from my ethnicity or heritage,” Ryan said. It’s not defiance or denial—it’s a man who has always measured himself against the music, not the room.

Which brings us to Charlotte. Ryan wasn’t even looking for the job when he first guest-conducted the orchestra. Post-covid, he was reimagining his career from “a place of maximum freedom.” But Charlotte had other plans. The city’s warmth embraced him. The orchestra’s musical chemistry with him was undeniable. And crucially, he genuinely liked his colleagues as human beings. “A workplace environment filled with mutual respect, trust and affection was so attractive to me that saying yes was easy,” Ryan expressed.

What Ryan brings to Charlotte goes beyond his baton technique or interpretive brilliance. When he conducts Brahms’ First Symphony — a piece he led at his first concert after his appointment was announced — he guides audiences through darkness into luminous joy. But his vision extends further. The Charlotte Symphony’s new CSO 360 series places the orchestra in the round, dissolving the traditional wall between musicians and listeners. It’s regularized through design.

At home, Ryan finds grounding in the everyday. He cooks with his Thermomix and air fryer, turning out curries and stews that combine his Trinidadian heritage with his love of efficient kitchen technology.

Ryan’s dream for Charlotte is elegantly simple: “A CSO playing at the height of its technical and creative powers for a large, faithful and appreciative audience that considers it the musical heart of our region.”

It’s the same vision that seven-year-old boy had watching Porgy and Bess — a belief that great music belongs to everyone, that the podium is exactly where he’s meant to stand, and that the most powerful performances emerge when artists stop proving themselves and start sharing themselves.

The conductor’s baton rises. Charlotte listens. And the music — oh, the music, speaks for itself.