Every three minutes, someone in the U.S. is diagnosed with blood cancer; worldwide it’s every 27 seconds. For many Black people diagnosed with blood-related illnesses like cancer (leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma) or sickle cell anemia — the most likely lifesaving treatment, a stem cell transplant, can be out of reach. The reason: a lack of registered Black donors. But DKMS, a global nonprofit that recently opened an office in Charlotte, is dedicating its resources to deleting the minority donor deficit.

Finding a match

Finding a donor-patient match isn’t easy. Matching is based on the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) tissue characteristics. HLA are proteins — also known as markers — found on most cells in the body. HLA is heavily influenced by genetics, which means a patient has a greater chance of finding a match with a family member. Problem solved, right? Ask family members to get tested. The problem is, in fact, not solved.

“We don’t share the exact same DNA with our family; there are some variations,” explained Maya Ward, public relations manager for DKMS. The reality is that 70 percent of patients must find a match outside of their family, she said.

“When a patient is in need of a match, the first step is to test their family members and hope they are a match. If they are not, then their physicians will search the global donor pool for a match,” said Ward.

Using the global donor pool, the objective is to find a donor of the same ethnicity. This is because certain genetic markers are often shared within the same ethnic background. For Black patients, the odds of a match are not in their favor. Minorities are underrepresented in the global donor pool.

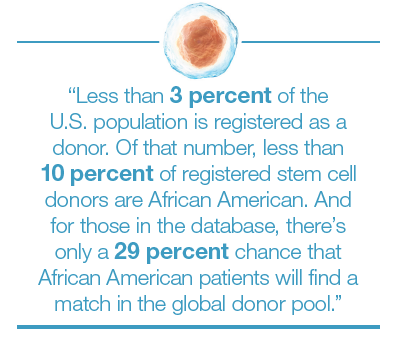

Less than 3 percent of the U.S. population is registered as a donor. Of that number, less than 10 percent of registered stem cell donors are African American. And for those in the database, there’s only a 29 percent chance that African-American patients will find a match in the global donor pool. The odds improve for Latinos/Hispanics to around a 48 percent chance of a match. White patients have a 79 percent chance of finding a match.

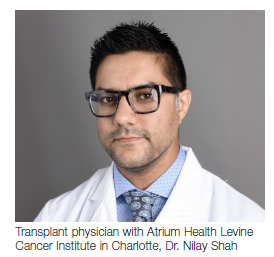

“For individuals who are minorities, we lack appropriate donor pools from around the world,” said Dr. Nilay Shah, transplant physician with Atrium Health Levine Cancer Institute in Charlotte. “We need more donors in the pool to allow for more patients to have a suitable donor and a chance at [a] cure.”

Removing the barriers to participation

Among the reasons for low minority donor representation is a historic lack of interest from the medical community.

“Historically, stem cell donor recruitment has not been targeted to these communities,” said Ward.

Black donors like Jasmine DeBerry Thompson are determined to help reduce the number of lives lost to blood diseases. When she was 16, Thompson found out a close friend was diagnosed with sickle cell and needed a stem cell transplant to live. Inspired, Thompson did everything she could to help her friend.

“When it came time for her to find a donor, [my community] hosted a drive, but I was too young to sign up. Our youth group did all we could to support her and her mom, but she passed away in 2010,” Thompson said. “Later, when I was in college, I was finally old enough to do something. So, I [registered] in her honor. I was blessed to be able to donate.”

A few years later at age 21, Thompson found out she was a match for another young girl who was also battling sickle cell. Thompson immediately agreed to the life-saving donation. Now 30, Thompson continues to advocate for more minority donors.

‘A second chance at life’

Donors like Thompson and organizations like DKMS are working overtime to highlight the need for minority stem cell donors. Thompson said it’s important that Blacks take time to consider that a cure for someone, “… may be in your veins. This is giving someone a second chance at life.”

According to Shah, “Newer therapies, improvements in existing therapies … and better understanding [of] expectations all contribute to our progress.” In addition to medical advancements, he stressed, “We have to avoid complacency. This requires increasing our awareness to these disorders.”

As part of its strategy to attract more people to the global donor pool, DKMS is offering free cheek swab kits by mail. Potential donors can visit www.dkms.org to request a kit. After the cheek swab, simply return the kit by mail. For those who go on to become donors, DKMS covers the costs, and lends support before, during and after the donation.

“I know oftentimes we have the mentality of, ‘What’s in it for me?’” said Thompson. “I believe God put us here to be helpers of one another. It’s that simple.”